By Alexandre Mies

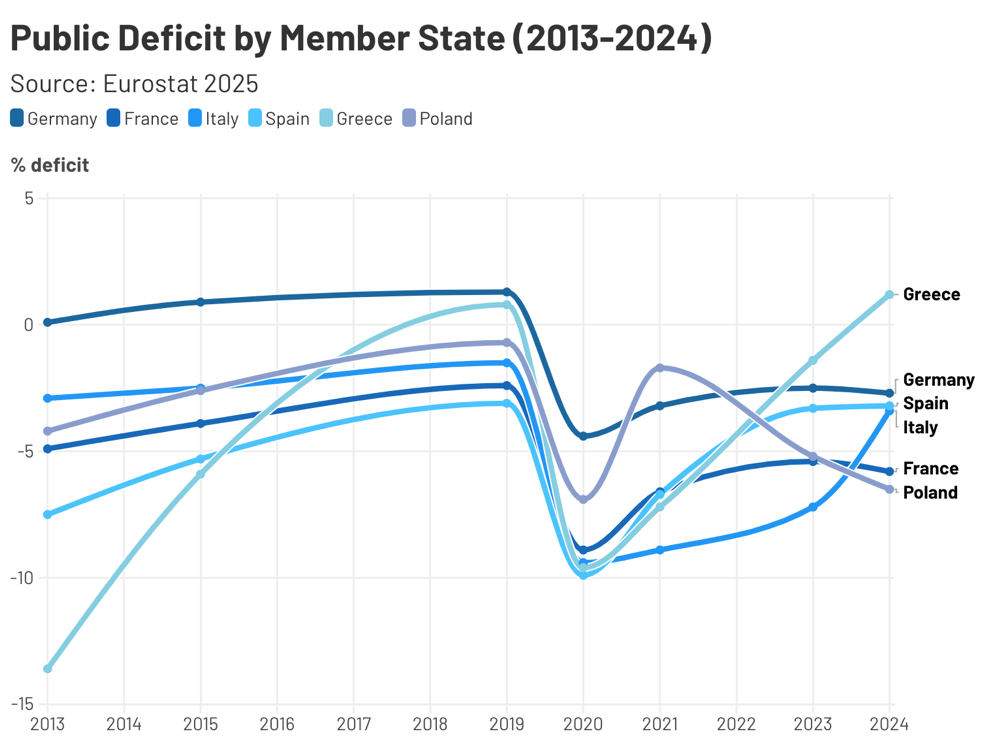

Since the eurozone crisis in the 2010s and especially since the Covid crisis, the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), or the Eurozone’s fiscal rules, increasingly revealed its limits. Before 2024, the SGP imposed the same quantitative budgetary rules on the 20 eurozone Member States, inherited from the 1992 Maastricht Treaty: public deficit below 3% of GDP, debt below 60% of GDP. In a “one-size-fits-all” approach, the SGP did not really take into account national specificities nor the economic cycle. The European Commission, in fact, supposedly applied automatic corrective and/or sanctioning procedures when thresholds were exceeded (even though large Member States like France and Germany often escaped sanctions in the early 2000s).

The 2024 Reform introduces negotiated national budgetary trajectories that better reflect national fiscal situations. Each Member State subject to the SGP now drafts a Medium-Term Fiscal-Structural Plan (MTP) taking its particular situation into account (debt, growth, needs of investment). Member States then have more room to negotiate these 4-7 year plans with the Commission, which must approve them.

As 2025 marks the first year in which the new rules are fully applied, Member States will decide their desired balance between fiscal consolidation and public investment in their upcoming MTPs. Still, the anchors of the SGP (the 3% and 60% rules) remain in place, even though many Member States were hoping for an easing in the rules. Long-term investments (green and digital transition, defence, etc.) also continue to be included in calculations for deficit and debt limits.

- After the Crises, the SGP Revealed Structural Weaknesses

The main problem with the pre-reform SGP was its rigidity: it encouraged procyclical budgetary policies during times of crisis. Instead of letting each Member State invest more when needed to stabilise their economy and protect populations (a countercyclical policy, per Keynesian economics), it compelled them to follow austerity procedures, thus aggravating the crises. During the eurozone crisis, for example, many Member States were forced to bring their deficits back under 3% even though they had low growth and high unemployment. Instead, most of these economies would have needed more public investments to get back to their pre-crisis growth trajectory.

During the Covid crisis and energy crisis, the general escape clause was activated from 2020 to 2024. This suspended the application of the SGP and let the Member States —even the “frugal” ones— invest to avoid massive recessions. This enabled a rapid and coordinated response: support packages for workers and companies, common borrowing through NextGenerationEU, etc.

Though, a structural reform seemed necessary from the beginning of the crisis, as the clause would not be permanent. Moreover, new EU priorities were adopted in the fields of green and digital transition, defence, competitiveness or industry. Also, the one-size-fits-all approach still represents a problem as great divergences exist in terms of public investment. For example, Poland is more dependent on fossil energies than Austria, which relies more on hydrogen and renewable energy. This creates divergent public needs, making the homogeneous budgetary trajectory almost absurd.

- Towards a More Comprehensive and Flexible Framework

At first glance, the new SGP framework seems to address the pre-2024 homogeneous approach problems. The new national MTPs replace the previous National Reform Programmes (NRPs), and entail a new model based on differentiation.

Now, each Member State proposes an MTP drawn up based on its specific characteristics, such as debt level, growth potential or considered investments. The Commission then negotiates and evaluates these trajectories, introducing an individual assessment of national budgetary policies. For the most indebted Member States, the Medium-Term Budgetary Objectives (MTOs) allow for a more gradual adjustment for the longer-term and does not impede constrained investments.

This model is considered more flexible in times of crises, as it takes into account exogenous shocks and the possibility to suspend or adjust constraints in case of serious circumstances. Also, the budgetary surveillance is no longer purely quantitative; it also takes the quality of the public expenditure into account (e.g. R&D, modernisation). This flexibility aims to avoid procyclical austerity and encourage support policies or investment, particularly when the economic conjuncture makes it necessary. For example, France and Belgium have benefited from a modulated post-Covid trajectory helping them avoid new austerity measures.

That said, the “qualitative” surveillance remains insufficiently considered in practice: green and digital investments are not included in the exemptions in deficit and debt calculations. Also, the flexibility remains contingent upon dialogue with the Commission and the institutional capacity to implement this margin for flexibility in case of future shocks.

- A Disappointing Reform: The Cost of Political Compromise?

Even though the MTPs represent a positive change for the SGP, the structural thresholds are still in place. It seems that this reform has been calibrated to be politically acceptable for both the European Parliament and the Member States. This reform is neither too conservative, as it offers more flexibility, nor too innovative either, as it does not truly implement more budgetary union or contracyclical policies.

On one hand, the reform maintains the Maastricht criteria, while many Member States were hoping for a real easing in the 3%/60% rules. In this way, both the surveillance and corrective arms of the SGP remain in case of non-respect of the rules. This perpetuates the “one-size-fits-all” approach and limits the “case-by-case” logic of the reform. Recent initiatives such as the ReArm Europe Plan or the Readiness 2030 White Paper show that defence investment will benefit from loosened constraints through a sectoral escape clause and new financial instruments. Interestingly, no equivalent rule is being discussed for climate or digital transition, despite large annual investment needs.

On the other hand, the reform increases complexity and discretionary power of the Commission. The assessment of national plans now relies on individual judgment based on negotiation with the States, potential growth or qualitative analysis. This may result in uneven application depending on the political dynamics between the Member States and the Commission.

Lastly, the reform does not focus enough on the EU’s investment gap, as it does not exclude long-term investment spending from the SGP’s deficit and debt calculations. This poses a risk of continued reductions in long-term investment (e.g., for green transition or social needs) to finance short-term budgetary adjustments if the economy decelerates.

Conclusion

To address the rigidity of the SGP during the last crises, the 2024 reform aims to allow greater differentiation in the Member States’ budgets. While the reform seems to bolster the credibility of the framework vis-à-vis markets and investors, it also introduces more complexity and more room for arbitrariness in the budget management.

Moreover, doubts persist whether the new SGP will be sufficiently transparent and understandable to the public, and whether it will be efficient in financing the important long-term investments required in the next years.

Today, budgetary rules are intrinsically linked to the EU’s global competitiveness challenges. Without an important increase of public investment in infrastructure, skills and climate, the EU risks falling behind the massive industrial support programmes of the United States and China.

About the author

Alexandre Mies is a Franco-Italian student studying Political Science at the College of Europe and Public Administration at Sciences Po Paris. With a double degree in History and Political Science, he has gained experience in several French and European administrations, where he has worked on budgetary, social and environmental issues.